STARTS

Mar 31, 2023

Ends

Apr 14, 2024

P24

Small Wonders

Small Wonders: The Formation of the Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures and their Evolution as an Art Form

A wedding present given to Martha Jane and John W. Starr in 1929 sparked a passion for portrait miniatures. The Starrs began exchanging them as gifts, continuing the longstanding tradition of these objects as intimate tokens of love, loss, allegiance and affection. By the late 1930s, they had become serious collectors, dedicated to acquiring a well-rounded group of exceptional American, European and, especially, British portraits, with one signed and dated example for every year British artist John Smart (1741-1811)ever painted. Their gift to the museum in 1958 and 1965 of nearly 300 portrait miniatures, forms the nucleus of the museum’s collection today.

These diminutive, jewel-like portraits, known during their early years of production in the 1500s, as ‘limning’s,’ had their roots in the elaborately gilded, colorful tradition of manuscript illumination from the 1400s. Portrait miniatures first appeared at the French and English courts in the 1520s. By the 1700s, their popularity was widespread beyond the crown and court, with miniature painters becoming established in major cities including London, Paris, and Boston. The invention of photography in 1839 led to a decline in portrait miniature production.

Produced in a variety of media and on a number of surfaces, below is a list of different materials that correspond to miniatures featured in this installation.

Vellum: The earliest miniatures were painted in watercolor on vellum, a translucent, fine animal skin adhered to the plain side of a playing card with starch paste. Playing cards not only provided a white surface, but added support. Artists ground their own colors into powder from minerals, plants, dried insect bodies and manufactured pigments often containing lead. These were mixed with a binding agent (gum Arabic) and water.

Plumbago: Towards the end of the 1600s, the plumbago portrait miniature emerged. Created using graphite on parchment or vellum, this monochrome portrait initially served as the basis for an engraving; however, by the 1700s it became an art form in its own right.

Ivory: Ivory replaced vellum as a support around 1707 and remained the primary support until the late 1800s. Chosen for its luminosity and ability to transmit that same quality to portraits, ivory is greasy and non-absorbent, thus making it a difficult support upon which to paint. Artists roughened the surface with powdered pumice stone and bleached it in the sun to make it whiter. had to roughen it up with a file and add more binding agents to their paint to get it to adhere.

Enamel: Considered a more robust alternative to ivory, enamel miniatures were painted on metal, usually gold or copper, and fired in a kiln. They required multiple firing processes and were very labor intensive. Their color was brilliant, however, and unlike watercolor, it did not fade.

The Starrs’ descendants have continued to honor their heritage with a gift of portrait miniatures in 2018, bringing new life to this beloved Kansas City treasure.

Organized by The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art

IMAGE CAPTIONS:

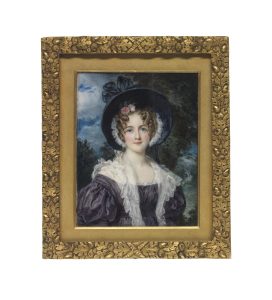

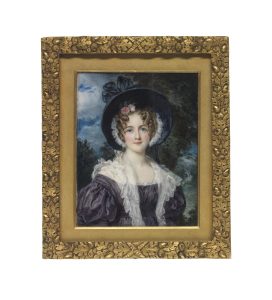

(left)William Charles Ross (English, 1794–1860), Portrait of Miss Mary Pack, 1832 Watercolor on ivory; Ormolu frame, 3 1/2 x 2 3/4 in. (8.89 x 6.985 cm) Inscribed on verso: “Painted by W.C. Ross / 1832 / Mary Pack / For my dear Flora / May 1883”. Gift from Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr and the Starr Foundation, Inc., F71-29/4

(center)Bernard Lens (English, 1681–1740), Portrait of a Woman with a Dog, ca. 1730, Watercolor on ivory; Gold and gold plate case with blue enamel front bezel and blue glass over embossed foil on rear. Overall: 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 in. (5.715 x 8.255 cm) Inscribed with monogram on recto, lower left: “BL” Gift from Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr and the Starr Foundation, Inc., F58-60/85

(right)John Smart (English, 1741–1811) Portrait of David Reid, 1802 Watercolor on ivory; Gilt copper alloy case with hair reserve and monogram, 3 5/8 × 2 3/4 inches (9.22 × 6.99 cm) Inscribed on recto, lower left: “J.S. / 1802” Inscribed with monogram on case verso, center: “DR”. Gift of James Philip Starr, 2018.11.1